Henry Lewis, graphic body

Or how a young Australian photographer manages to photograph only himself without playing the self-portrait.

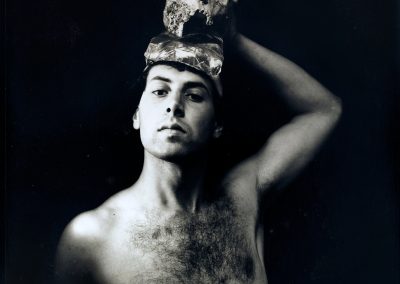

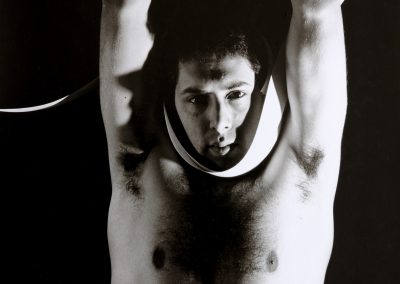

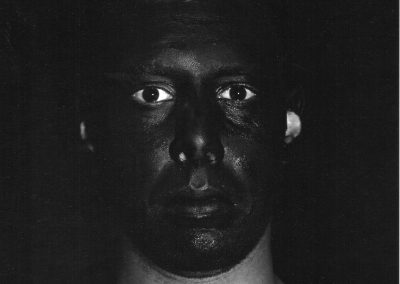

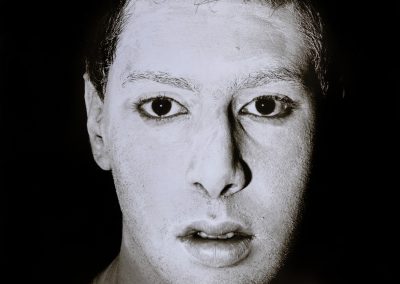

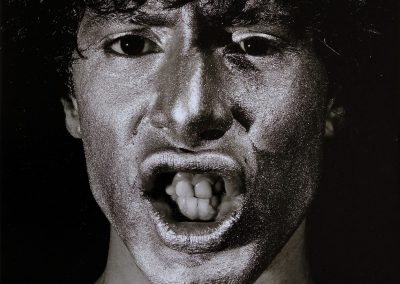

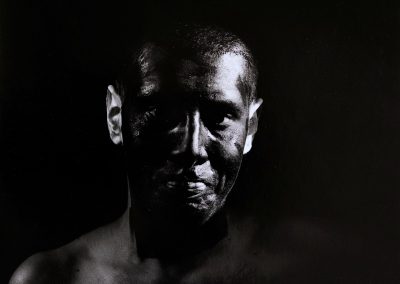

The prints are large, very large, in black and white. The frames are hung from the picture rails by long black ties that pull them like the image is pulled from the body. The images are simple and obvious, made of minimal events, harmonized with white paper, hands, outstretched arms, illuminated torsos and faces barely protruding, with fixed gazes. Everything lies in the tension, in an uneasiness that imposes itself as a rite, proof, or demonstration, with an unabashed desire to make an image. Henry Lewis has established himself as one of the four or five “young people” working in France on staged photography. There is no question, however, of trying to assimilate him to any current because the world of this Australian who has been living in Provence for several years is strictly personal, to the point that he uses only himself in his images. At once model and operator, subject, author and director, Lewis avoids narcissistic pitfalls because he is only interested in the photography. And not just any photography.

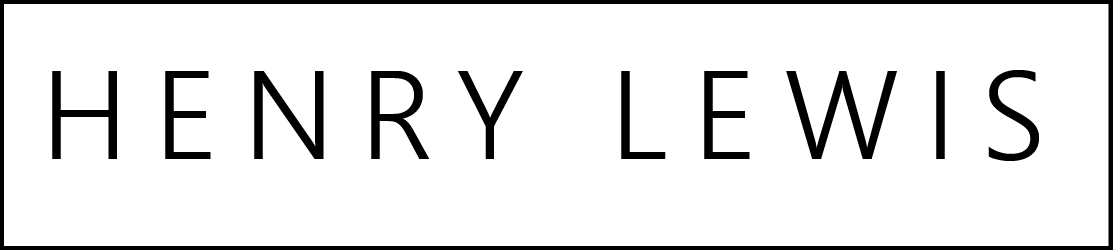

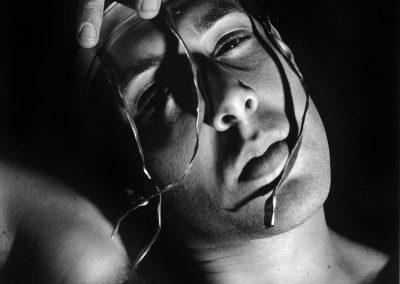

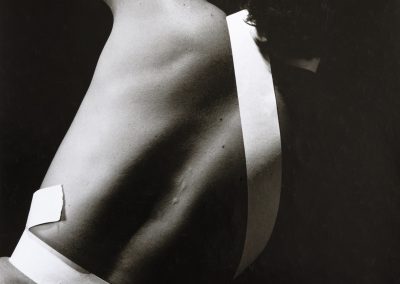

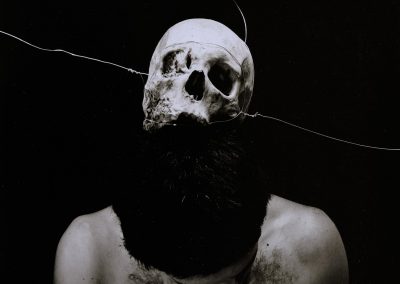

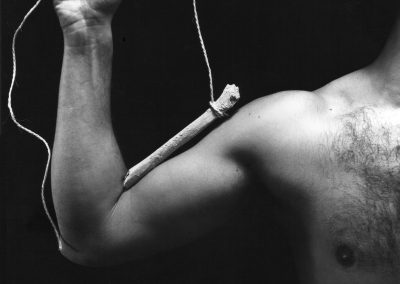

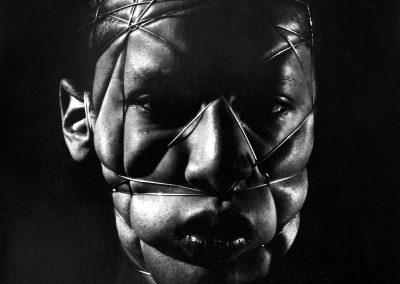

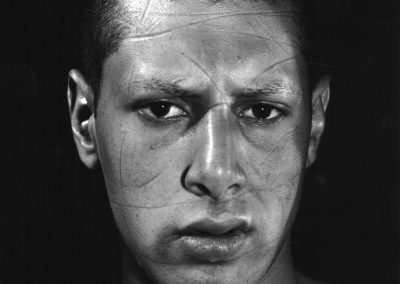

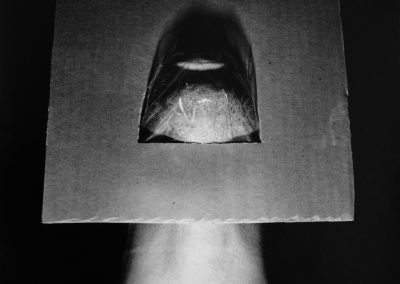

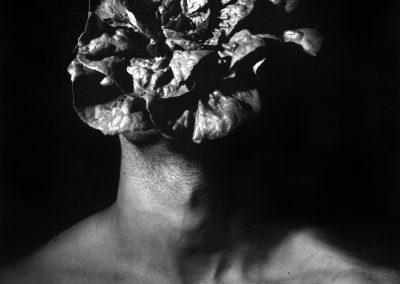

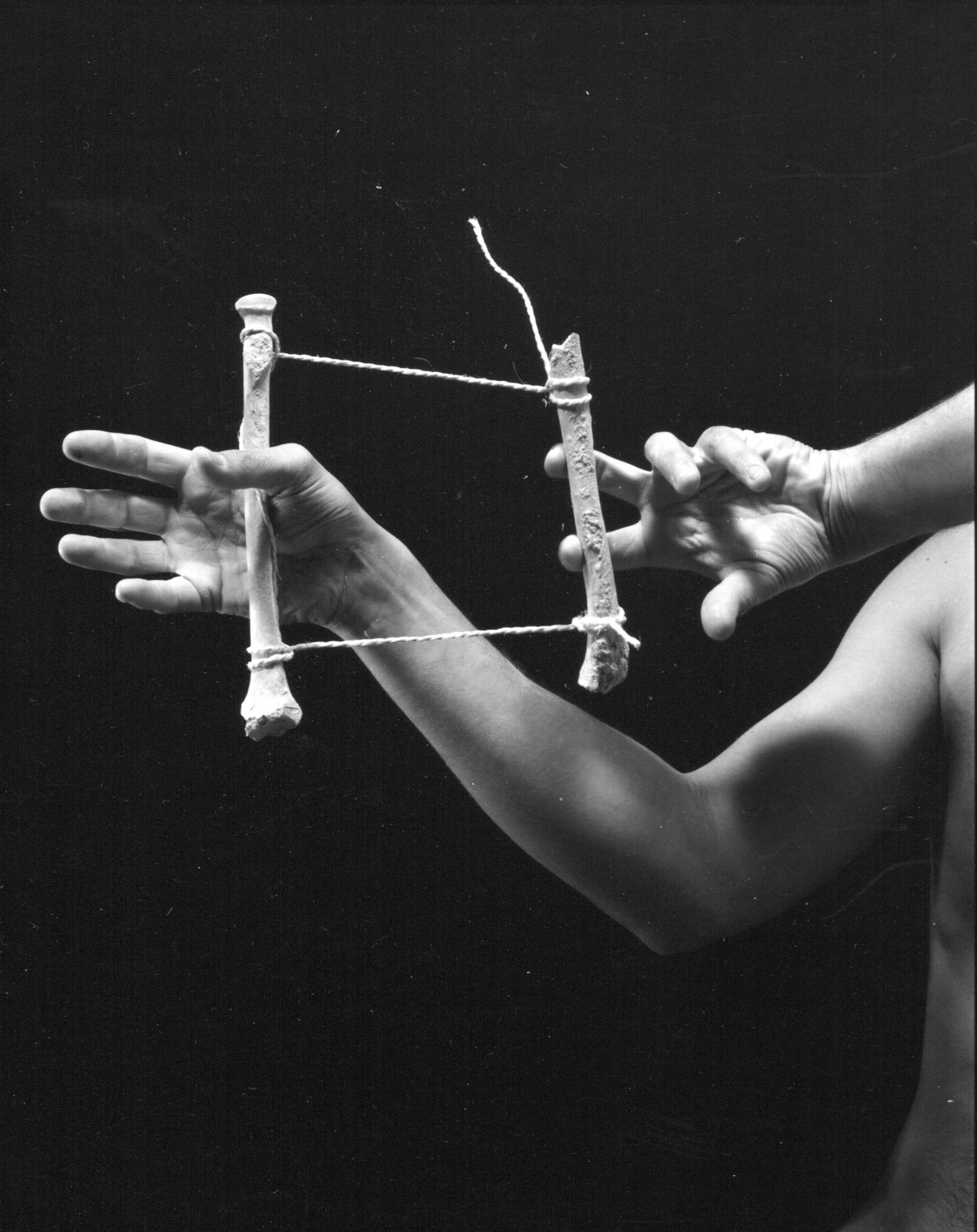

One remembers a first series of portraits that were not self-portraits – unless one considers them in an approach that should appeal to psychoanalysis and identity problems – even if each image called upon the photographer’s face. Bruised portraits tied up with paper, mouths taped with tape, photographs that are both mute and blind, skulls shaved, disfigured and violently lit portraying fixed expressions and sometimes disturbing poses. Already, the ritual, almost auto-sadistic, the violent black and white and the splendour of the prints. Then came the hands, bandaged and compressed, almost stumps, but poetic, sometimes transformed into plants or flowers on a black background. The very large format prints then commenced, offering a breathing space between the depths of black and of the layout. The present series naturally unfolds, showing the face surrounded by white paper strips on a torso that the deceptive low lighting makes look ill-proportioned. This fixed gaze, the dramatic lighting, the evocation of the body suspended by the hands [absent from the frame] and the play of metaphors leave one feeling a little uneasy. There is no explanation, no desire for discourse, just signs that could perhaps lead to a story. But the photographer will say no more. He is content to hang his images on the wall for you to get caught up in. Less harsh, still playing with illusion and metaphor on a black background, a series of outstretched or folded arms mimic gestures, tensions, towards inaccessible objects outside the frame. Rolled or unrolled strips of paper accordions on which the light modulates construct graphics, articulating themselves on the diagonal, and beginnings of parallel paths. There is play and ritual, much that is unspoken, a childish and perverse taste for mystery, a calm way of asserting without demonstrating that is disturbing, as is the strength of the signature on such minimal effects.

Portrait, self-portrait. The temptation is great, often, to rely on this type of production to reiterate the eternal questions of artistic identity. But, with Henry Lewis telling us so little, always fearing in the inflated and timorous images, the contradiction becomes irrelevant. The ellipsis simply affirms black and white, architectural and allusive games. The refusal of the self-portrait, which is not so far from the colour simulacra dear to Cindy Sherman, even if the tonality is totally different, is based on an elegy of anguish, on an apparent distance between the image but we cannot believe or think that it is him. The confusion thus created is all the more seductive because of the certainty that is created. We will never know who he is, looking at the physical theatrics of Henry Lewis on the black curtain of the background. And we will know all the less because he uses himself as model; his self-portraits are his best self-defence, the images his mask.

Christian Caujolle. May 2 1984

(Translation from French)

Kleine Geschichten wie Traumsequenzen – Small Stories like Dream Sequences

Modern man, who directs his own destiny with confidence and a capacity for knowledge, who consciously creates, invents and sees through himself, offers little in the way of art. He also corresponds less and less to our image of the present, which entangles man in contexts he does not understand; he appears as a driven man, a victim. The symbolic power of the subconscious is experiencing a renaissance.

This is also the case in the photographic works of the young Australian Henry Lewis, which can be seen in the Swidbert Gallery. The exhibition shows a number of large-format black-and-white photographs, all of which live from a connection between body and matter. In a sequence of four images, we see an arm playing with a long, bright ribbon. But the game seems to develop into a fight, the ribbon winds around the wrist, the scenery suddenly seems threatening. In the last photograph, the arm appears as if it has been extinguished; throwing the ribbon away, it clenches its fist as if in triumph. Lewis’s works tell of small layers, they seem like dream sequences.

In another group of four works, he varies the motif of a man’s head with bright bands. Sometimes these look like jewellery, sometimes like a curtain, finally like a cage or muzzle. The man is interchangeable; Lewis shows his facial features blurred, out of focus.

This depersonalisation also becomes clear in two works that show the upper body of a man whose head is wrapped in paper bands. But this rather depressive motif seems almost like a game in the next picture, because the man seems to be able to loosen the bands, to free himself.

Liberation, however, does not seem possible in one of the most expressive works in the exhibition: two hands held up as if helplessly are guided by long threads attached to the individual fingers. Man as a marionette – every movement, no matter how small and exact, is controlled by others?

Ralph Fleischhauer 10 December 1985

(Translation from German)

Henry Lewis: image list: The Body, 1977-1985

This work stated in Sydney and continued during my time in the US and France. They were first printed in 30cm x 40cm format and then enlarged further to 94 x 127cm after 1981. Exhibitions were presented in galleries and museums in Europe, Australia and the U.S. A.

1801 San Francisco, 1978: 30 cm x 40 cm. In collections: Amsterdam, Le Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, Bibliotheque National, Paris.

1802 San Francisco, 1978. 30 cm x 40 cm: Collection: Amsterdam, Le Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, Bibliotheque National, Paris.

5805 San Francisco, 1978: 30 cm x 40 cm. Collection: Le Bibliotheque National, Paris

8808:a,b,c (triptych)

San Francisco, 1979: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B (1981): 126 x 309 cm. Collection of Musée d’art moderne et contemporain de Saint-Étienne, Le Bibliotheque National, Paris.

9794 San Francisco, 1978: 30 cm x 40 cm

28013 San Francisco, 1979: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B (1981): 94cm x 127 cm.

38015 San Francisco, 1978: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B (1981): 94cm x 127 cm.

68032 San Francisco, 1978: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm: Le Bibliotheque National, Paris, edition B (1981): 94cm x 127 cm.

4801 San Francisco, 1979: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm: Le Bibliotheque National, Paris, edition B (1981): 94cm x 127 cm.

4807 San Francisco, 1979: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm: Le Bibliotheque National, Paris, edition B (1981): 94cm x 127 cm.

58025 San Francisco, 1979: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B (1981): 94cm x 127 cm.

58038 San Francisco, 1979: 30 cm x 40 cm : Le Bibliotheque National, Paris.

38026 Forcalquier, 1981: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm: Le Bibliotheque National, Paris, edition B (1981): 94cm x 127 cm.

7819 Forcalquier, 1981: 30 cm x 40 cm: Le Bibliotheque National, Paris.

88126 Forcalquier, 1981: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B (1981): 94cm x 127 cm.

108117 Forcalquier, 1981: 30 cm x 40 cm: Le Bibliotheque National, Paris, edition B (1981): 94cm x 127 cm

118114 Forcalquier, 1981: 30 cm x 40 cm

3822 Forcalquier, 1982: 30 cm x 40 cm

48221 Forcalquier, 1982: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B: 94cm x 127 cm.

58217 Forcalquier, 1982: 30 cm x 40 cm: Le Bibliotheque National, Paris

5839 Forcalquier, 1983: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B: 94cm x 127 cm.

8837 Forcalquier, 1983: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B: 94cm x 127 cm.

8838 Forcalquier, 1983: 30 cm x 40 cm.

58315 Forcalquier, 1983: 30 cm x 40 cm.

58340 Forcalquier, 1983: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B: 94cm x 127 cm.

68320 Forcalquier, 1983: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm: Le Bibliotheque National, Paris, edition B: 94cm x 127 cm.

88218 Forcalquier, 1983: 30 cm x 40 cm.

88341 Forcalquier, 1983: 30 cm x 40 cm.

1848 Forcalquier, 1984: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B: 94cm x 127 cm.

8849 Forcalquier, 1984: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B: 94cm x 127 cm.

18417 Forcalquier, 1984: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B: 94cm x 127 cm.

18430 Forcalquier, 1984: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B: 94cm x 127 cm.

18445 Forcalquier, 1984: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B: 94cm x 127 cm.

88441 Forcalquier, 1984: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B: 94cm x 127 cm.

1985 Forcalquier, 1985: 40cm x 50cm

38515 Forcalquier, 1985: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B: 94cm x 127 cm.

38525 Forcalquier, 1985: Edition A: 30 cm x 40 cm, edition B: 94cm x 127 cm.