Breathing, The Breath of the Artist

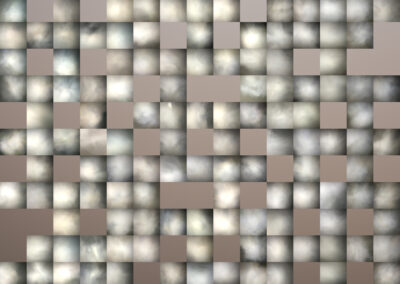

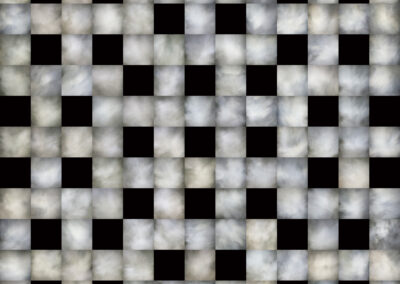

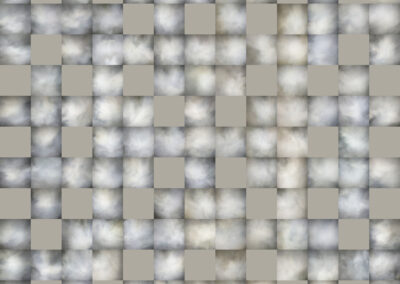

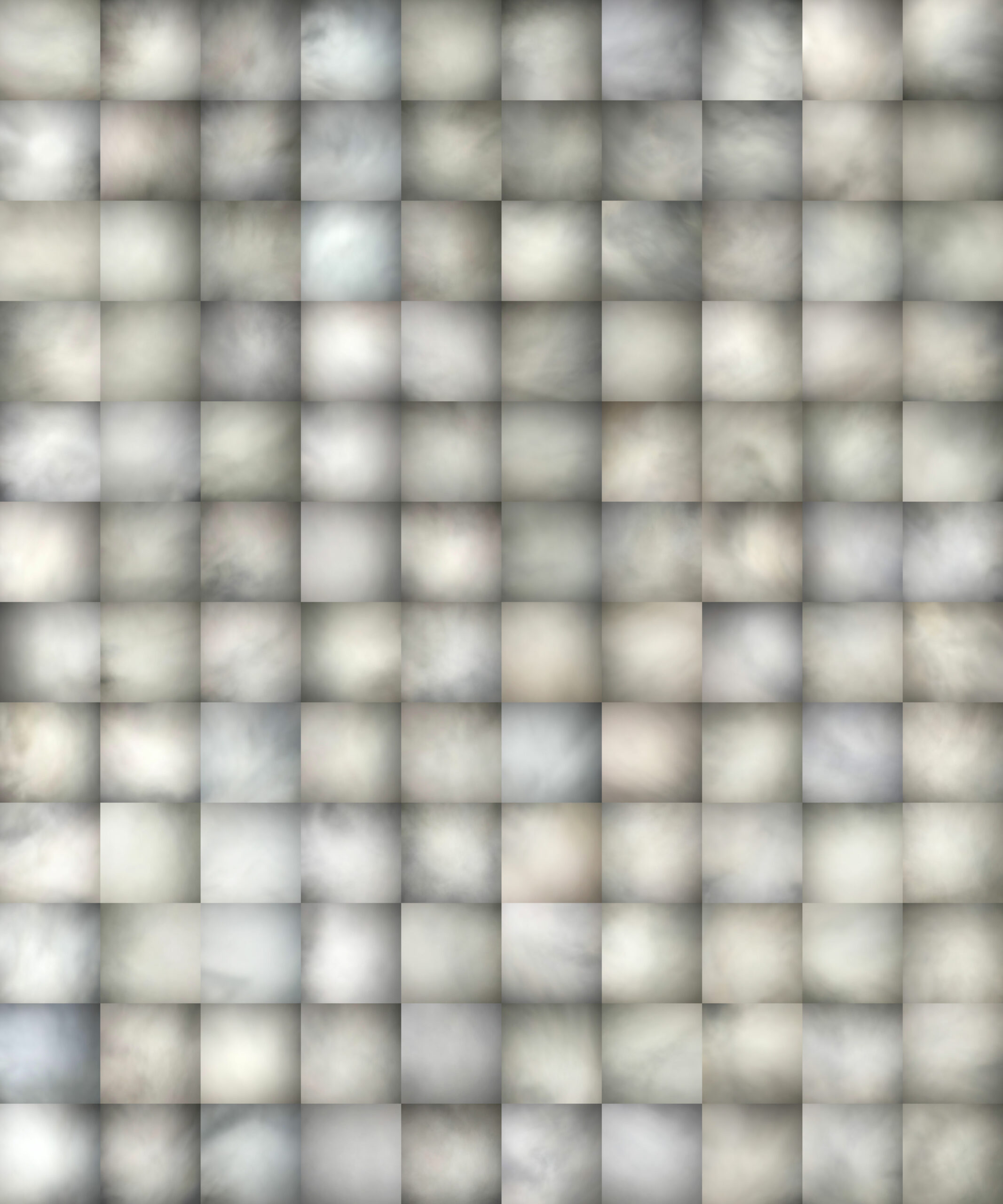

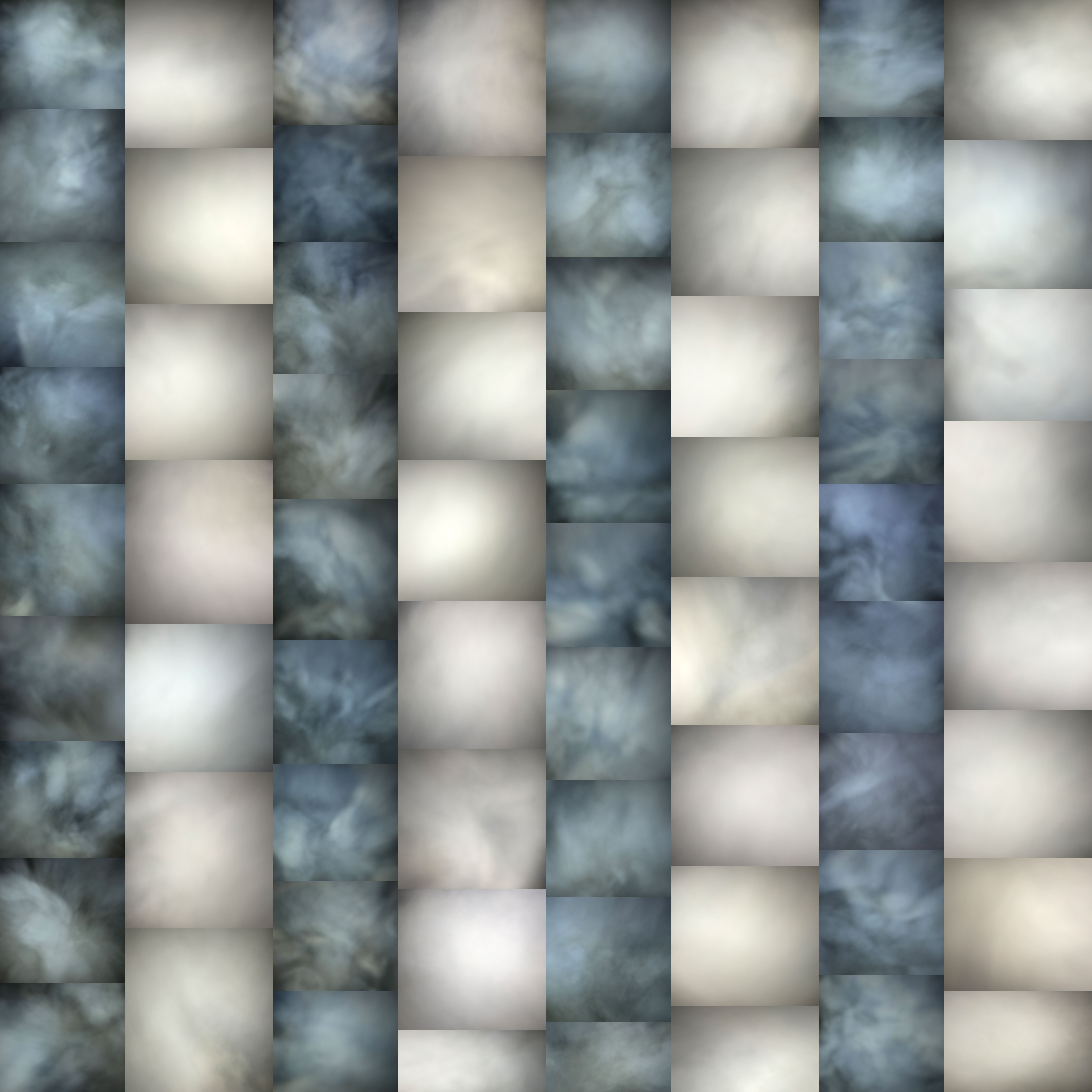

Little puffs of condensing air make up this work – Breathing, The Breath of the Artist. The observation of a cycle, as repetitive as it is ephemeral, is a necessity occurring for every human being around 14 times per minute. This is incessant, ad infinitum, or at least until one’s end. The act of breathing is so banal that the contradiction has moved me to cherish each manifestation like an epiphany. I have preferred not to merely document the phenomenon but rather “capture” a trace of exhalations, redeploying them into the piece. The subjects were observed and captured at night; laden with condensation therefore they appeared visible [to photography]. I have collected these views, objectivizing them before they expired and are forgotten which occurs throughout humanity billions of times every second. I like the idea that something so insignificant might metamorphose into something substantial. An ephemeral phenomenon has become immaterial. Through the assemblage of these images, the subject has become a doppelganger that exists separately and has an existence long after the original exhalations have dissipated into the atmosphere. Their origin has become but a memory. Do we remember what we were feeling at the time of each breath or is our memory clouded with our passing history. Questioning might urge us to retrace the past context of that history or rather progress to the present; everybody has their impulses.

In and ex: Henry Lewis’s Breathing

Breath. We hold it. We qualify and describe it. But we seldom see it, and even more frequently – except in the most extreme cases – think about it. But breathing is integral to our lives. We do it unconsciously, or at least autonomically, or, in certain instances, it can be mapped, programmed, and repeated mechanically. It maps time, from our first breath to last, dying breath. Yet the outcome, breath, is far less significant than its process, breathing. We’re concerned should it not happen, but indifferent to its manifestations.

Henry Lewis begs to differ. Across thousands of images, he has tracked this generally invisible process. Photographed the remainder (invisible, rather than indivisible) to shine a light on what all too often occurs within and simultaneously out of view.

Being aware of our “being” always seems to be a revelation, as in the quixotic amusement of “seeing one’s breath.” But variation is where Lewis sees, captures, and chronicles value. We may not breathe in the same way, or other influences may impact how we do. And in chronicling the variations within and between his own breathing, Lewis highlights how little we understand or engage with the ubiquity and fragility of the process. At its simplest, we lack the capacity to understand not the process, but its products. A well-known probability calculation suggests that there is a 98.2% chance that every breath contains a molecule from Julius Caesar’s dying breath. Here this potential is simply isolated at 1/20,000th of a second.

So, when Lewis documents the differences and repetitions of this singularly universal process, he calls into question the significance of variation. The French philosopher Gilles Deleuze invited us to think of these minute variations closely, suggesting that only a thing or things that are alike can differ, and only in their differences do they truly become alike.

Lewis’s works push this assertion toward its logical conclusion. By beginning with a universal, autonomic, experience, then capturing its unpredictability again and again, Lewis constructs his metaphor for what seems identical but is its own opposite at precisely the same time. Yes, every image captures breathing, but each captures its own unique breath. That they’re all Lewis’s only unifies them both on their surface (him) and in their subject, but none could or can ever be identical.

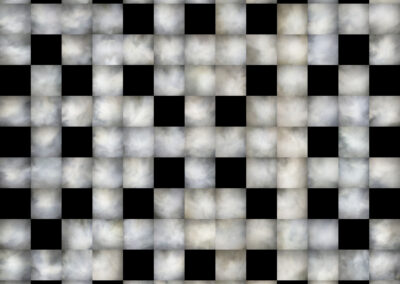

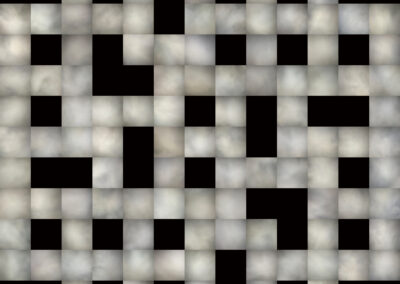

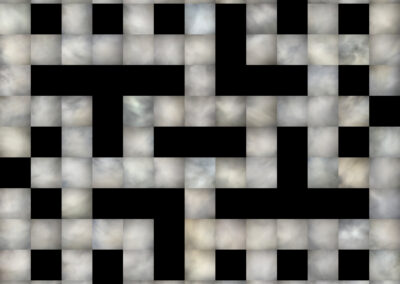

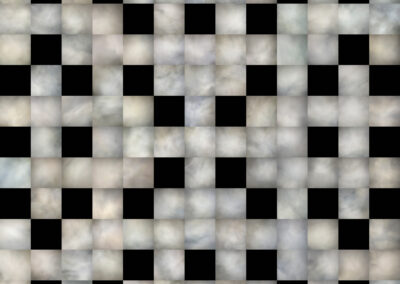

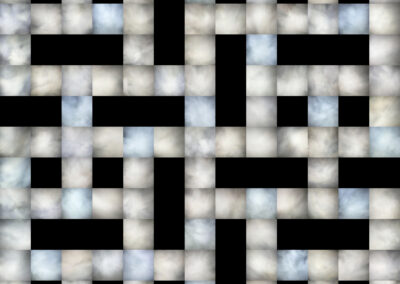

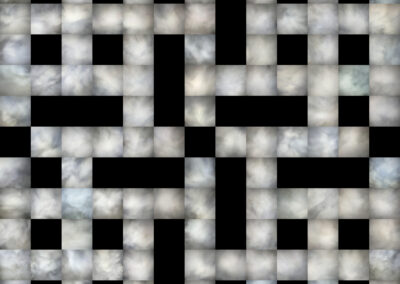

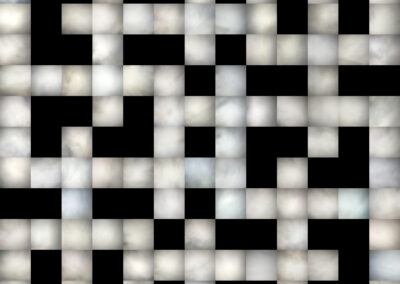

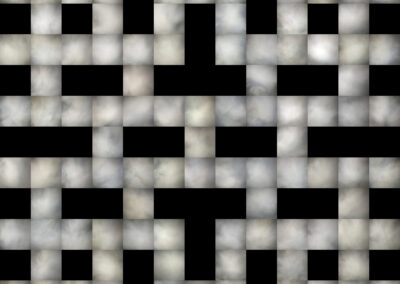

To make this distinction more visible, Lewis uses the metaphor of the crossword puzzle. Squares within a square, the puzzle’s variations seem internal: clues; language; blank and black spaces. Each guide us toward a solution. But just as we scratch out an incorrect answer, Lewis invites us to see how that which seems persistent, or predictable, is anything but. Yet what makes these works most alluring, and truly transformative, is how we’re able to see, find, and experience both difference and familiarity within every frame. It is not so much that it mirrors viewers’ breaths as it is that we all breathe; it is not so much that perhaps we could find words to describe a single image, but that we might find it within ourselves to look closely enough to see variation revealed. The one with more darkness; the one that seems fuller; the one that seems frozen in time, left to hang in the air.

This duality, between the works’ solidity and the effervescence and impermanence of what they capture, is one of Lewis’s recurring themes. As he remarked in an interview on his earlier x-ray works, where he described how technology brought what might have formally been invisible to the fore, “We are dealing with the concept of transferal…although this realm is very much in existence, everywhere around us like climbing into space.” The space we are invited into here may very much be personal, private, and but for the intersections of technology, imperceptible, but within each fragment and each frame, each singular image creating its own unique manifestation of the same, we find shared understandings, shared values, shared perceptions, and shared experiences. While we may lack the capacity to put what we see into words, we can rest well assured in its simple, universal, and endless meaning: breathing.

Brett Levine October,2023

“Brett M. Levine is an independent curator and writer currently living and working in the U.S.”